|

At 53, earning

$300,000 a picture, he pooh-poohs his romantic charm

-- and calls

himself a "large, economy package of acting"

For the last 25 years,

a tall, dark, handsome and apparently ageless fellow has sauntered

through the dreams of female moviegoers. His brow and chin

are cleft sharply, as if by a sabre cut. He has spindle

shanks, a muscular torso, a perpetual tan (beach in summer, sun

lamp in winter), dazzling white teeth, and coarse iron-gray

hair. His voice is pleasantly rough, with nasal overtones;

his eyes are black, deep-set, and usually worried.

Cary Archibald

Alexander Leach Grant is able to use these physical attributes

with all the dexterity of a magician flipping a card out of the

air.

A shrug and a grin, he

is boyishly irresistible. A frown and a tightened

cheek-muscle, he is the stout adventurer. A yell and a

sprawl, he is the uproarious comedian. A whisper and a twinkle,

he is the romantic lover.

This 53-year-old actor

handles his multiple characterizations with the ease of a trained

chameleon. He refuses to believe that his personal

attraction is responsible for his ever-blooming stardom.

"Of course, sex

appeal, looks and all that get mixed up in it," he says

disarmingly, "but really, the director who hires me gets the

large, economy package of acting. I'm still on top

simply because I save the studios money."

Grant explains this

curious claim with an expert pantomime of what he means.

"suppose I'm doing the simplest thing: speaking a line to

someone off-camera. The director tells me to take a drink of

iced tea at the same time. That presents a thousand

problems.

"If I bring the

glass up too soon, I sound like a man hollering into a

barrel. If I put it in front of my mouth, I spoil my

expression. If I put it down hard, I kill a word on the

sound track; if I don't, I make it seem unreal. I have to

hold the glass at a slight angle to keep reflections out of the

lens. It has to be absolutely still to keep the ice from

tinkling since you can't use cellophane substitutes in the close-ups.

And finally, I have to remember to keep my head up because I have

a double chin!"

He points out that

using a movie novice who didn't know all this -- however

experienced an actor he might be otherwise -- could cause a delay

of hours in shooting time where each lost minute runs into

thousands of dollars.

Grant, who gets

$300,000 a picture, has been in the high tax brackets for the last

18 years. "Out of each $100,000," he says, "I

take home exactly $13,000. Even at those bargain prices I

like to work. I'm proud of being an expert screen

actor."

The kind of poise that

Grant typifies on the screen has not been easy for him to come

by. A sensitive man, inclined to be wary of the world but

desperately wanting to be friendly, he has come to the conclusion,

after more than 60 movies, that privacy is the single luxury a

movie star cannot afford.

As an actor, however,

he is anxious to have the public on his side. In the early  days of his career, he fretted away his evenings in cheap hotel

rooms, trying to analyze why people laughed or sighed at certain

words and gestures. Later, as a star, he made it a habit to

sneak into the back row at one of his own pictures and discover

firsthand exactly what bits of theatrics got a good response.

days of his career, he fretted away his evenings in cheap hotel

rooms, trying to analyze why people laughed or sighed at certain

words and gestures. Later, as a star, he made it a habit to

sneak into the back row at one of his own pictures and discover

firsthand exactly what bits of theatrics got a good response.

"I've got a whole

headful of push-button tricks," he says. "But the

best way to get the sympathy of an audience is to get yourself

into a jam and let them help you wangle your way out. A

kindly chuckle is the actor's best old-age insurance."

On the other hand,

Grant loathes the individual parts of an audience. Assailed

by autograph fans, he has been known to deliver a short,

impassioned address urging them to go back to kindergarten, then

sullenly sign his name.

He has an easily

roused temper and is capable of such great concentration that it

often appears to be an exhibition of selfishness. Grant

thinks his two marriage failures -- his first to an actress,

Virginia Cherrill, in 1934, and to Barbara Hutton, one of the

world's richest girls -- can be attributed to the fact that

"I thought too much about my career and not enough about

them."

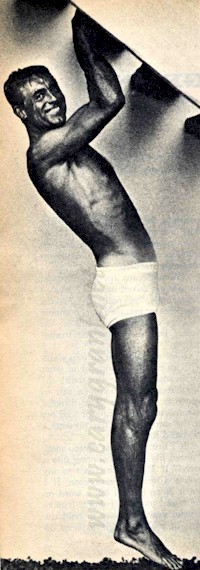

The muscular Grant torso is made more so by chinning on a

staircase at home.

"I was

emotionally immature," Grant says humbly. "I

persisted in my stupidities." It is on such occasions

that he exhibits an unnatural gallantry toward the other sex -- a

trait which seeps through on film and endears him to all women. As

for the three-year Hutton affair, the accepted explanation is that

"the socialities around the heiress couldn't take the actors

around the husband." Whatever broke up these romances,

it did not create the usual aversion. The

rebound from the Hutton fiasco was three years behind him when he

saw a young actress-writer, Betsy Drake, playing in a London hit

show, Deep Are the Roots. Her evocative performance

impressed him. Grant

got her the lead opposite himself in his next picture. He

astounded the camera-conscious crowd by allowing her to fudge most

of the footage. They were married in Arizona on Christmas

Day, 1949, with Howard Hughes - and old friend - as best

man. The match has been a highly successful one ever since. His

pert, attractive wife - with the personality of a dedicated pixy -

has had much more influence on Grant than most people know.

She has settled him down to less drinking and practically no

smoking. She has given him a stability and comfort that he

never knew. At

their unpretentious Palm Springs house, Grant spends a good deal

of time soaking up the sun and getting his tan, exercising his

undeniably excellent physique, and chivvying his wife about her

writing - something she has been working at earnestly. He is

openly proud of her efforts in this direction. His wife

smiles mysteriously and says little, a fact that occasionally

makes her voluble and efficient husband apprehensive. The

fact is that Grant is precise and methodical enough to make him a

hard customer to live with. He does not care to have bits

and pieces lying around - everything he does, from perfectionism

in acting to dandyism in the way he dresses, fulfills this complex

of tidiness, which is possibly a reaction to the helter-skelter

commencement of his career. Though

he was born on January 18, 1904, in the respectable suburbs of

Bristol, England, in a well-to-do family, he likes to think of

himself as a cockney. He can shift effortlessly from classic

English to a spray of aspirates. He has a habit of emitting

low greetings to people high in his estimation - such as " 'Ow

are'e, Jymes?" or "Gor bless 'e, Al; 'ow's the mussus?"

This knack dates back to his first theatrical job, that of a

knockabout comedian in an English vaudeville troupe.

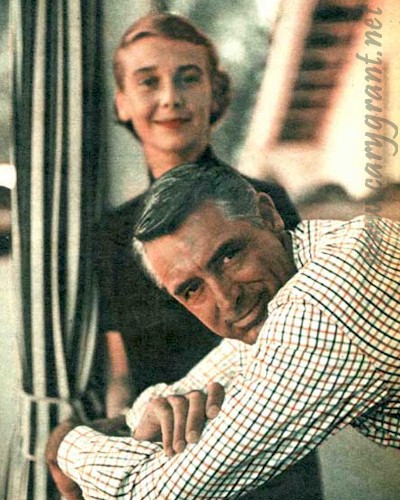

Now happily wed, he says of his previous two marriages,

"I was emotionally immature."

The

group of zanies was called Bob Pender's - a rowdy collection of

impromptu violence. It featured manic stilt-walking,

eccentric dancing and slapstick comedy. Young

Archie Leach became a Penderite over his family's indignant

protests. His father, Elias Leach, was securely settled in

textile manufacturing. "I

wanted to travel and have an easy life," Grant says.

"I though acting was the easiest life possible and it would

give me a chance to travel as much as I pleased." To

avoid arguments - something which he still hates - young Leach

slipped out of the house and joined the Penders at the age of

13. A month later, his father discovered his whereabouts and

wheedled him back home. Sadly, he resumed his studies for a

year and a half at a swank academy - and then had to gratify his

itch for the theater once more. This time his family bade

him good riddance and Archie was on his way. By

1921, the fame of the Penders had spread far enough for them to

shuffle across the sea and do an act in New York. As the

eager yes-sir man of the troupe, young Leach was still soaking up

hard knocks. He was a gangling 17, on his way to

six-foot-one, with tight curly black hair, a highly ingratiating

manner, and winning ways with the girls. The next year the

Penders went back to England but Archie - enchanted with the

bustle of New York - stayed. For

two years he tried just to remain alive - shilling at sideshows,

painting neckties, even walking stilts with billboards on his back

at Coney Island. He

returned to England for two years, then was signed for a juvenile

lead in a New York musical called Golden Dawn. Archie

- as he was still known - went on to roles in Polly, Boom-Boom,

Wonderful Night and finally as the hoarsely romantic

baritone in The Street Singer. No one noticed him in

the slightest. Determined

to shed the light of his personality, he played the lead in a

dozen operettas in St. Louis Missouri, summer stock. Still

unknown, he returned to Broadway and got a job in a romp called Nikki. "I'd

been on exhibition for five years - and I felt like a squirrel in

a cage," Grant says. He announced he needed a vacation,

packed his white tie and tails, and left for the West Coast

in a second-hand car. He has never appeared on stage since. He

demonstrated his will to survive by haunting agents and casting

offices in Hollywood, living in rundown hotels and taking long

walks to dispel his pessimism. He changed his name to Cary

(from a name in a play) and Grant (found in the telephone

book). He got his first job as a javelin-tossing husband in This

is the Night, in 1932. His dark good looks and height,

plus his spontaneous manner, won him successive roles in Hot Saturday,

Merrily We Go to Hell, and Blonde Venus with Marlene

Dietrich. The first picture in which he had what he

considered a meaty part was She Done Him Wrong with Mae

West. He learned

from Miss West, he says, "nearly everything I needed" -

and this, added to the days of the Pender training, was enough to

catapult him upward. He still thinks that Miss West is the

top actress of all time. By

1940, Grant had played upper and lower parts in an estimated 30

films, nearly all for Paramount. Somewhere about that time,

he discovered he had acquired a unique gift. It was one

which few actors possess: "tickling up" a line until it

comes to life. He

found himself by quitting his Paramount contract in 1937 with an

alibi: "I was getting all the roles Gary Cooper didn't

want. I didn't feel that Gary and Cary should be

confused." Most

likely Grant wanted to resume his lone-wolf career, confident of

his ability to get along. He went over to Columbia for

$75,000 to do a picture called The Awful Truth with Irene

Dunne - that has now become a comedy classic - and went on to do Topper,

Bringing Up Baby and the first version of The

Philadelphia Story. "It's

wonderful to hear people laugh in unison," he says.

"I get more of a kick out of that than any kind of

acting."

Grant is one of the few people who can take a custard pie in the

face and not appear ridiculous. "I try to be the man in

trouble who should know better," he says. To keep

himself on top of a situation, Grant always uses a great deal of

pantomime, absorbed from his early knockabout days. He

got to do drab, serious things such as None but the Lonely

Heart and psychological melodramas like Suspicion and Notorious.

His salary went up to the top of his career in 1947 when Samuel

Goldwyn paid him his $300,000 asking price to play an

earth-visiting angle in The Bishop's Wife, and then tacked

on an extra $100,000 for additional work. At the time it

constituted an all-time salary record for a single picture. Though

it is remarkable how many movie hits of taste and quality Grant

has participated in - such as Destination Tokyo, His Girl Friday,

Dream Wife, To Catch a Thief - it is equally remarkable that he

has never won an Academy Award. At least six of the pictures

in which he has starred have brought Oscars to his co-workers, but

nothing for Grant. "There's

such a thing as doing your job too well," says one

friend. "Cary fits in so neatly on film that the

audience gets to noticing what he does rather than what he is.

This kind of anonymity is the hallmark of great talent - but it

doesn't win any awards." No

one knows how much Grant cares about recognition. Having

been on the top for 20 years, with his salary still at its

highest, he appears to be enjoying life as much as ever. He

has little time to pore over the 20 scrapbooks which constitute

his concession to ego. He

visited Spain last year and did an expert portrayal of an effete

English naval officer who gets caught up in the anti-Napoleonic

fervor of 1810. In the picture, The Pride and the Passion,

a production top-heavy with extras and costume trimmings, his role

was calculated to bring him critical applause. Coming home

from that affray, he launched himself instantly into An Affair

to Remember, with Deborah Kerr. Although

Grant allegedly despises his own face - he usually hangs his

pictures in the bathroom - his acutely aware of its cash

value. He recently hired a valet, a 33-year-old named Sam

Lewis who fought Archie Moore and lost with a close decision, on

the basis of a single sentence. :He endeared himself to me

instantly, "says Grant, "by telling me that I looked no

older than he did." "All

actors are shy," says Grant, "at least I am."

He welcomes the opportunity to put on a role he does in

disguise. "Sometimes I can get pretty tired of

myself." His alternate remedy is to seize his wife and

some suitcases and trek off to a spot where he is relatively

unknown to the natives. Though

he can safely be called middle-aged, Grant is far from losing the

enthusiasm and energy which has always characterized him.

His present despair with the modern world is that there seems to

be no more of his type of comedy. "It's the highest

from of art, to write a good comedy," he exclaims.

"People used to be able to write this kind of thing because

they had time - and because they lived with grace, they wrote with

grace." This

kind of challenge - which Grant is continually meeting - has faced

him ever since he slipped out of his bedroom window 40 years ago

on his way to join the Penders. It is very important to him

to meet life on its own terms - and triumph over it by the

exercise of gallantry and grace. "Otherwise,"

he says, "there is not much point in living at all, is

there?"

|