|

The

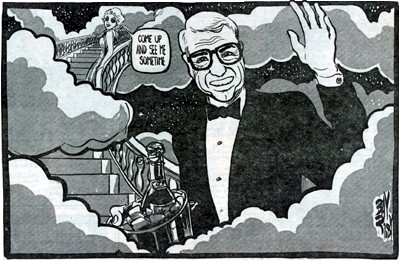

following are several articles from the New York Post on 12/1/86, in

tribute to Cary's death.

He

was a trouper to the very end

-- by Joy Cook; pgs. 2 & 12

Cary Grant died a

trouper's death, collapsing of a massive stroke just moments after

rehearsing for a road show performance in Middle America.

He had charmed the stagehands and

fiddled with the microphones, a perfectionist to the end.

The 82-year-old silver-haired star, who made the term

debonair a personal trademark, died six hours after his backstage

collapse Saturday night in the Mississippi River town of Davenport,

Iowa.

"He had been his old chipper self. He made several

stage changes to improve the performance during rehearsal, to improve

the enjoyment of his audience," said Lois Jacklin, director of the

group that arranged the 90-minute film clip and question period, "A

Conversation with Cary Grant.

White

House and Hollywood mourn loss

-- by Jack Schermerhorn; pg. 2

Cary Grant, the

leading man of some of Hollywood's finest films, was remembered by

President Reagan as a man whose "elegance, wit and charm will

endure forever on film and in our hearts."

"Nancy and I are very saddened by the death of our very dear

and longtime friend," Regan said as he returned to Washington from

a Thanksgiving holiday at his California ranch.

"We will always cherish the memory of his warmth, his

loyalty and his friendship.

"He was one of the great people in the movie business,"

said Jimmy Stewart, who starred with Grant in "The

Philadelphia Story."

"I am saddened by the loss of one of the dearest friends I

ever had," said Frank Sinatra. "I have nothing more to

say except that I shall miss him terribly."

"He was one of the greats -- in the same league with Clark

Gable and Spencer Tracy," said comedian George Burns.

"He was one of my heroes," said Dean Martin.

"He was not only a great actor, he was a refined and polished

gentleman. We were very close friends, and I'm going to miss

him."

"He was the most handsome, witty, and stylish leading man

both on and off the screen. I adored him and it's a sad loss for

all of us," said Oscar-winning actress Eva Marie Saint, who

appeared with Grant in Alfred Hitchcock's thriller "North By

Northwest" in 1959.

Alexis Smith, a leading lady of the 1940's and '50s who played

opposite Grant in 1946's "Night and Day," remembered him

fondly.

"I think he was the best movie actor that ever was," said

Miss Smith. "There's a term 'romance with a camera,' and I

doubt anybody had as great a romance with the camera as he did."

"Cary Grant was surely as unique as any film star and as

important as anyone since Charlie Chaplin," said Charlton Heston.

"We have just lost the man who showed Hollywood and the

world what the word class really means," said Emmy-winning actress

Polly Bergen.

"He was the one star that even other stars were in awe

of."

The

Secrets Behind the Charm

-- Roger Ebert; pgs. 4 & 57-58

Everyone knows that

Cary Grant was the most charming man in the history of the movies, but

charm alone did not make him a star, and indeed he rarely offered only

charm in a performance.

There was always something underneath, a quiet reserve, a certain

coldness, a feeling that he was evaluating his leading ladies even as he

romanced them, and that dual nature is what made him so important in so

many different kinds of films.

He brought comedy to thrillers, danger to romance, and even a

certain poignancy to slapstick farce. He always gave us more than

we bargained for.

Look, for example, at his famous kissing scene with Ingrid

Bergman in Hitchcock's "Notorious" (1946). In the movie,

they are in love with each other, but Grant is a U.S. intelligence

official trying to convince Bergman to marry Claude Rains, the

leader of a postwar Nazi spy ring.

Hitchcock's shot begins on a balcony overlooking Rio. Grant

begins to kiss Bergman, and as they stay in each other's arms, they move

slowly inside, where Grant picks up the telephone and makes a call,

still holding her and kissing her, and then he guides them toward the

door while she breathlessly makes dinner plans and he smiles rather remotely

at her and then leaves, saying "goodbye" with an ironic smile.

This is the kind of scene that perfectly captures what was unique

about Grant as a movie actor. He had the kind of handsome

charm and sex appeal that made him completely convincing as a

romantic leading man, but mere seduction never seemed very high

on his list of priorities in the movies. He and

his characters often had hidden agendas, secrets they were more interested

in than love itself.

In "Notorious," Grant cold-heartedly sends the woman he

loves into a marriage with a Nazi and then cuts off communication with

her because he thinks she has turned into a drunken slut (actually, she

is dazed because the Nazis are slipping arsenic into her coffee).

Another leading man might have wanted to appear in a better

light, would have protested against such cruel behavior.

But Grant seemed to welcome ambiguity; although he appeared in a

lot of formula movies, he rarely played a formula character. Often

he is effective in a movie just because he is playing against the other

acting styles on the screen, keeping a poker face through a comedy and

then dropping light-hearted wisecracks into a suspense

picture.

Whatever and whoever he played, Grant was almost always recognizable

as himself in a move; he didn't go in for disguises and prop

noses. That led some critics to assume that he was always playing

himself. In a way, they were right; but what Grant himself tried

to explain was that even "Cary Grant" was a role he was

playing.

"I first created an image for myself on a screen, and then

played it off-screen as well," he once said.

In his 1983 book on Grant, Richard Schickel wrote:

"The screen character he created started sometime in the mid-1930s drew

on almost nothing from his autobiography, but was created almost

entirely out of his fantasies of what he would like to have been from

the start."

The start, for Grant, was a long way from what he became.

Born Archibald Leach in 1904 in Bristol, England, he was the only

child of a possessive mother and a withdrawn father. His parents

were unhappily married, and the key psychological event in his life

occurred when he was 9, and came home from school one day to find that

his mother was no longer there.

At first he was told she had gone on holiday, and then that she

had gone somewhere on a long visit.

Only 20 years later did he learn that she had been committed to a

mental institution, "by which time," he once said, "my

name was changed and I was a full-grown man living in America, known to

most people of the world by sight and by name, yet not to my

mother."

Is it too much to assume that his childhood trauma, the

unexplained departure of his mother, colored all of his thoughts toward

women, and gave a deeper, even sinister dimension to his performances?

He played opposite many of the greatest actresses of his age,

from Mae West, who gave him his first starring role in "She Done

Him Wrong" (1932), to Katharine Hepburn, who was his favorite

partner in the 1930s, to Audrey Hepburn in "Charade" (1964),

when he was deciding to retire from the movies. One thread runs

through many of his screen romances: He spent more time being pursued by

women than pursuing them, and he sometimes used an aloof, teasing comic

style to keep them at arm's length.

The character he played in those movies was often much the same,

and could be called "Cary Grant," a name he made up himself,

the first name from a role in a school play, the second from a list

supplied by the studio.

He was born into an English society which was much more

class-conscious than it is now, and he was not born a

"gentleman."

His father was part Jewish, a pants-presser for a garment

manufacturer, and his mother came from modest origins as well.

Grant was an ill-behaved schoolboy; he ran away at 13 to become

an acrobat, and worked his way up through vaudeville in England

and America before emerging, in the 1930s, as the quintessential

mid-Atlantic gentleman.

It was a role he had learned to play, he sometimes suggested, by

studying men he admired; eventually, the role became so comfortable that

he began to inhabit it off-screen as well, until he and the role became

the same.

Because Grant was a definitive movie star, his actual acting

ability was often overlooked. Yet in David Thomson's respected

"Biographical Dictionary of Film," there is a flat statement::

"He is the best most important actor in the history of the

cinema."

Thomson justifies this praise by pointing to Grant's

"unrivaled sense of timing, encouragement of fellow actors and the

ability to cram words or expressions in gaps so small that most other

actors would rest."

He had, Thomson adds, "a technical command that is so

complete it is barely noticeable."

That technical command is best seen in Grant's comedies, where

his timing was so perfect that other actors never seemed wittier than

when they were in a scene with him.

Look at Grant opposite Rosalind Russell in Howard Hawks'

"His Girl Friday" (1940), the remake of the classic Chicago

newspaper comedy in which machine-gun dialog is rattled off nonstop for

90 minutes.

Then look at him opposite Katharine Hepburn in "Bringing Up

Baby" (1938), in which her dog steals his priceless dinosaur bone

and gives it to her pet leopard, which Grant chases until he

catches Hepburn, instead.

Both movies fall into the genre of screwball comedy, and might

play on the same double bill, but notice how Grant modulates his

performances, especially in the crucial scenes where he realizes that he

may be falling in love.

It is an actors' truism that comedy is harder to play than

tragedy, and perhaps no one in movie history could have played those two

roles, and many others, better than Grant.

He was also the perfect foil for Hitchcock in a movie like

"North by Northwest" (1959), with its gloriously absurd

plot. Here Grant's ability to play against the material was

crucial to the success of the movie.

Hitchcock set out to place his hero in one fantastic location

after another: Grant is almost shot in the UN, chased by an airplane in

an open field, and ends up dangling from the faces of Mount

Rushmore. A serious performance here would have been

comical. A comic performance would have undermined the movie's

genuine suspense.

Who but Grant could have found the just right note, halfway

between drama and farce? The movie might not have worked at all,

except in the way Hitchcock and Grant made it work, by marching straight

ahead through the plot.

In real life, if such a term can be used about Grant's

life, he was one of the few stars whose name could be shortened into one

word, "carygrant," and used as a shorthand incantation to

represent a whole attitude about life. There are only a few such

words made out of names, "marilynmonroe," "johnwayne."

For some moviegoers that represents a way of looking at things.

"Who do you think you are," people ask. "Cary

Grant?" By which everyone knows exactly what they mean.

His

Somber Words

-- by Cindy Adams; pgs. 4-5

Cary Grant once

talked me to me of death.

It was May 1982. He mentioned that he knew it was not so

very far off. Said Grant quietly: "One approaches death

with reluctance and trepidation. I suppose one always approaches

with fear what one doesn't know.

"On a recent trip East the airline was playing 'On Golden

Pond.' I stopped watching it. I told myself it was because

I wanted my wife to see that movie with me. But in truth ... I

think the main reason was that Henry Fonda's aging character reminded

me of me."

We were in his suite at the Waldorf Towers. He opened the

door himself and we sat alone for the afternoon.

In those days Grant was Faberge's "Goodwill Ambassador."

He explained away the job description with:

"The use of my name doesn't harm the company and I'm

permitted to do whatever I choose. They ask can I be someplace

and I say yes or no. People flock to actors. And the

movies are like any other business. Then end result is to please

the public.

"Why are people surprised when actors are

intelligent? Actors must be bright or they couldn't make the

money they do. People think acting is called, 'Anybody can do

it.' So why doesn't everyone go ahead and do it?

"It's because he was an actor that Ronald Reagan managed

the position he has now. The man had a crash education. We

all did."

Cary Grant was super gracious except for one thing. When

I phoned him he had set the ground rules. No photographs.

I couldn't even bring a photographer near the hotel.

I asked our mutual friend, Faberge's then chairman, George

Barrie, for help. Forget it. Interview, yes. Photo,

no.

When he'd attend public events in his elegant Hong Kong-made

tux, flashbulbs popped. So why not now? Because, Cary

insisted, that was different. But a real photo -- posed on a

casual afternoon -- no. The man looked better than I did.

Smelled better than I did. I even told him that. Forget

it. No pictures.

I asked about that famous apocryphal Mae West statement.

A hundred years ago she had supposedly discovered him and

purred: "If that Grant guy can talk I'll take

him."

Said Cary: "Not true. She didn't discover

me. I'd made four pictures before I met Mae. Mae West was

never known to tell the truth."

He was aware he was a monument, sort of an early Mount

Rushmore. "In Northwest, Alfred Hitchcock actually wanted

me to do a scene on Mt. Rushmore. He wanted me to sneeze inside

Lincoln's nostril. But we didn't because he couldn't work out

that echo."

Cary Grant did not watch his films. "I don't want

to. Some are 40 years old. The stuff's tinny now. I

know that's me there, the man I was, that reed-thin man with the black

hair ... I know that's me, but it's not me now."

Nor did he watch TV much. He said he loved the news,

"60-Minutes," and baseball games. He said that his one unfulfilled

ambition was to be a commentator at a baseball game "for only an

inning or two."

He is never going to get that chance.

In

Life He Was Larger Than His Image On Screen

-- by Ray Kerrison

The only time I saw

Cary Grant was when he and Fred Astaire went out to Hollywood Park two

years ago to be inducted into the racetrack's Pavilion of the Stars.

Grant was 80 years of age at that time. He wore a dark

blue suit, black-rimmed glasses perched on his nose, and his hair

shone white.

When he walked into his glitzy new building with his wife

Barbara, I half expected to see a doddering old man in his twilight,

an old star dimming against the clock.

What I saw was something else, something never to be

forgotten. Grant walked into that building tall, straight as a

redwood, elegant, sure of foot, smiling and radiating a presence I

have never before -- or since -- experienced.

In the flesh, movie stars have a habit of shrinking back to our

size. Cary Grant was the only movie star in my experience who

seemed to loom larger than life than his image on the screen.

Women that morning stopped in their tracks. Men gaped and

stared. Electricity rippled through the crowd.

Here was an old man being feted like a young matinee idol.

Grant made a brief, little speech. I don't remember a

word he said in that distinctive accent because, like everyone else, I

was too engrossed wondering how a man of 80 could look so young,

vigorous and in command.

Grant was a director of Hollywood Park, a good friend of its

proprietor, Marje Everett. Her track has always been the track

of the stars, going back to 1938 when the Hollywood Turf Club was

formed under the chairmanship of Jack Warner. Its 600 original

shareholders included Al Jolson and Raoul Walsh (two of the original

directors), Joan Blondell, Ronald Colman, Walt Disney, Bing Crosby,

Sam Goldwyn, Darryl Zanuck, Ralph Bellamy, Hal Wallis, Anatole Litvak

and Mervyn LeRoy.

LeRoy brought his friend, Grant, to the Hollywood board in 1977.

At the track yesterday, Mrs. Everett fought to retain her

composure. "We're all stunned," she said.

"We are in mourning for Cary. A nicer person we will never

meet.

"Cary came out to the track last week and I had never seen

him looking so well. I mean, he was sparkling.

"He told me how he planned to spend Thanksgiving with

Jennifer (his daughter, a student at Stanford University) and then go

out to the Midwest for question-and-answer stage show at a couple of

universities.

"He loved this kind of thing because, basically, he was an

extremely shy man."

Grant was a member of Hollywood Park's marketing committee.

"He was a very bright fellow," Mrs. Everett

said. "He had a feel for what people wanted.

"The only directors meetings he ever missed were those

held when he was out of town. He supported me generously.

I loved him, he was a marvelous human being and so modest."

Mrs. Everett said nothing impressed her so much about Cary

Grant as his thoughtfulness and concern for ordinary people.

"I have a friend who is very ill," said Mrs.

Everett. "Yet Cary always found the time to be interested

and thoughtful. There was never an opening day here that he did

not send me flowers or candy with a handwritten not. All the

employees loved him.

"He gave joy to everyone."

Of how many may this be said? Can a man ever have a

sweeter epitaph? The tens of millions who grew up in the postwar

period, going to Cary Grant movies will agree with Mrs. Everett and

more.

He glowed in a gentler age, when wit and charm and manners were

fashionable and desirable. It's probably no coincidence that his

screen career ended in the '60s, the decade that blew apart with

violent demonstrations, disenchantments, disruptions and, ultimately,

a coarseness that is still with us.

There is not much demand for Cary Grants these days and that is

our loss.

Grant's private life was a far cry from the suave, soothing

characters he played on screen. He endured his share of

tortures: his mother was admitted to a mental institution; he ran away

from home at 13; he took five wives; he experimented with LSD.

But his films were distinguished by their tact and taste, good

fun, intrigue and romance. Men and women alike responded to his

touch.

You can't say, "They don't make them like Cary Grant

anymore" because the did not make them like him before he came

along. He was the only one of his kind.

Flashes

& sounds: indelible images of a superstar

-- by Jerry Talmer; pg. 57

Two images, two

sounds -- two among a million -- flash into the head upon the death of a

man like Cary Grant.

One is his laughing-on-the-straight delivery of the word

"Tulsa." The other is the sound of a bird cage being

smashed. In "The Awful Truth" (1937), on of the

greatest of movie comedies, Cary and Irene Dunne, that dashing couple,

are getting divorced, even if they still have the hots for one

another.

She's been going out on the town with Ralph Bellamy, a visiting

cowboy-oilman-rube from Oklahoma. In fact she's told the world

she's going to marry Bellamy.

Now, in a nightclub, Cary Grant sits himself down at her and

Bellamy's tiny table and makes hearty small talk about how great it's

going to be for her in her new life in Oklahoma City, or wherever.

"And if you get bored," he finally says, "you can always

to to Tul-sa for the weekend."

That's one sound. In his voice. Sublime.

The bird cage is the one smashed by Ernie Mott in his mother's

hockshop in London East End of "None But the Lonely Heart"

(1944). Ernie is Cary Grant. Ethel Barrymore is his

mother. The bird, a canary, has been hocked for a few farthings by

a sort of Cockney bag woman of that era. It is the only thing in

the world she has and loves. When she comes to reclaim it, it is

dead in its cage.

And Ernie explodes. He can't stand squeezing the poor any

longer, can't stand the entire system of class structure and greed and gangsters

and fascism and the dark night closing in. This was Cary Grant's

most serious movie, by Clifford Odets out of Richard Llewellyn, and

little thanks the actor got for it. The reviewers all pointed out

he was maybe 20 years too old to play Ernie Mott. But he wanted to

do it. It was where he'd come from.

That movie haunted Bob Burdick -- a fellow in fact I think from

Oklahoma, and the nosegunner on my B-24 -- all through WWII. It

haunts me still. The best movie I saw this year, "Mona

Lisa," is about an Ernie Mott of the 1980s. I hope Cary Grant

got to see it before he went.

|